Abstract — LLMs are increasingly used to assist with scientific research, but can they actually do science? We evaluate 12 frontier models on a benchmark inspired by Eleusis, a card game where players deduce a hidden rule through experimentation, a microcosm of the scientific method. Each turn, the model proposes a card, receives feedback, refines its hypothesis, and decides whether to commit to a guess. Performance varies dramatically, but the key finding is surprising: raw reasoning ability isn’t enough. Models exhibit distinct “scientist personalities” (cautious, bold, or balanced) that determine success almost as much as their ability to find the answer. All models show significant overconfidence that impairs their ability to achieve a better score. These results suggest that for LLMs to truly assist with science, they need not just logical ability, but metacognition, that is knowing when they know enough to act.

Large language models are now routinely used for scientific research, to analyze data, generate hypotheses, even design experiments (Wang et al., 2023; Boiko et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2024). But how well do they actually embody the scientific method?

Benchmarks like ARC-AGI (Chollet, 2019) test inductive reasoning, asking the model to infer patterns from examples: they present fixed evidence and expect a single answer. But the scientific method is usually not an isolated inference step, it is more of an iterative process of observation, hypothesis formation, experimentation, feedback, and refinement. It of course requires logical ability, but also strategic judgment: which experiment to run next, when evidence suffices to commit, whether to keep exploring or converge on a theory.

And beyond logic and strategy, scientific research involves psychological factors rarely evaluated in AI. Calibration: does my confidence match my accuracy? Metacognition: how aware am I of my own uncertainty (Flavell, 1979)? And resistance to confirmation bias, the tendency to seek only supporting evidence (Wason, 1960; Nickerson, 1998). A brilliant scientist who is overconfident in weak theories will waste resources pursuing dead ends.

To test whether LLMs exhibit these deeper aspects of scientific reasoning, we turned to Eleusis, a 1950s card game designed by Robert Abbott (Abbott, 1977; Gardner, 1977) as a simulation of scientific discovery. In the original game, one player invents a secret rule governing which cards can be played; others must deduce it through experimentation. The rule is a hidden law of nature, each card play is an experiment, and the sequence of accepted and rejected cards is the accumulating evidence. Eleusis is a microcosm of the scientific method (Romesburg, 1979), with clear ground truth and unambiguous feedback.

We built a benchmark around Eleusis to ask: can models act like scientists? Can they form and refine hypotheses, design informative experiments, calibrate their confidence, and know when they’ve gathered enough evidence to commit?

These skills matter beyond the laboratory. Debugging code, diagnosing patients, navigating everyday uncertainty: all demand the same iterative cycle of hypothesis and test. Understanding where models succeed and fail at this process tells us something about their readiness for open-ended reasoning in the real world.

1. The Eleusis Benchmark

We adapted Eleusis into a single-player benchmark focused purely on scientific reasoning. The game has previously been used as a testbed for inductive learning in AI (Dietterich, 1980). The original game involves multiple players competing to deduce the rule fastest, with scoring that rewards efficiency and penalizes wrong guesses. By removing the multi-player dynamics, we isolate the core challenge: hypothesis formation and testing under uncertainty.

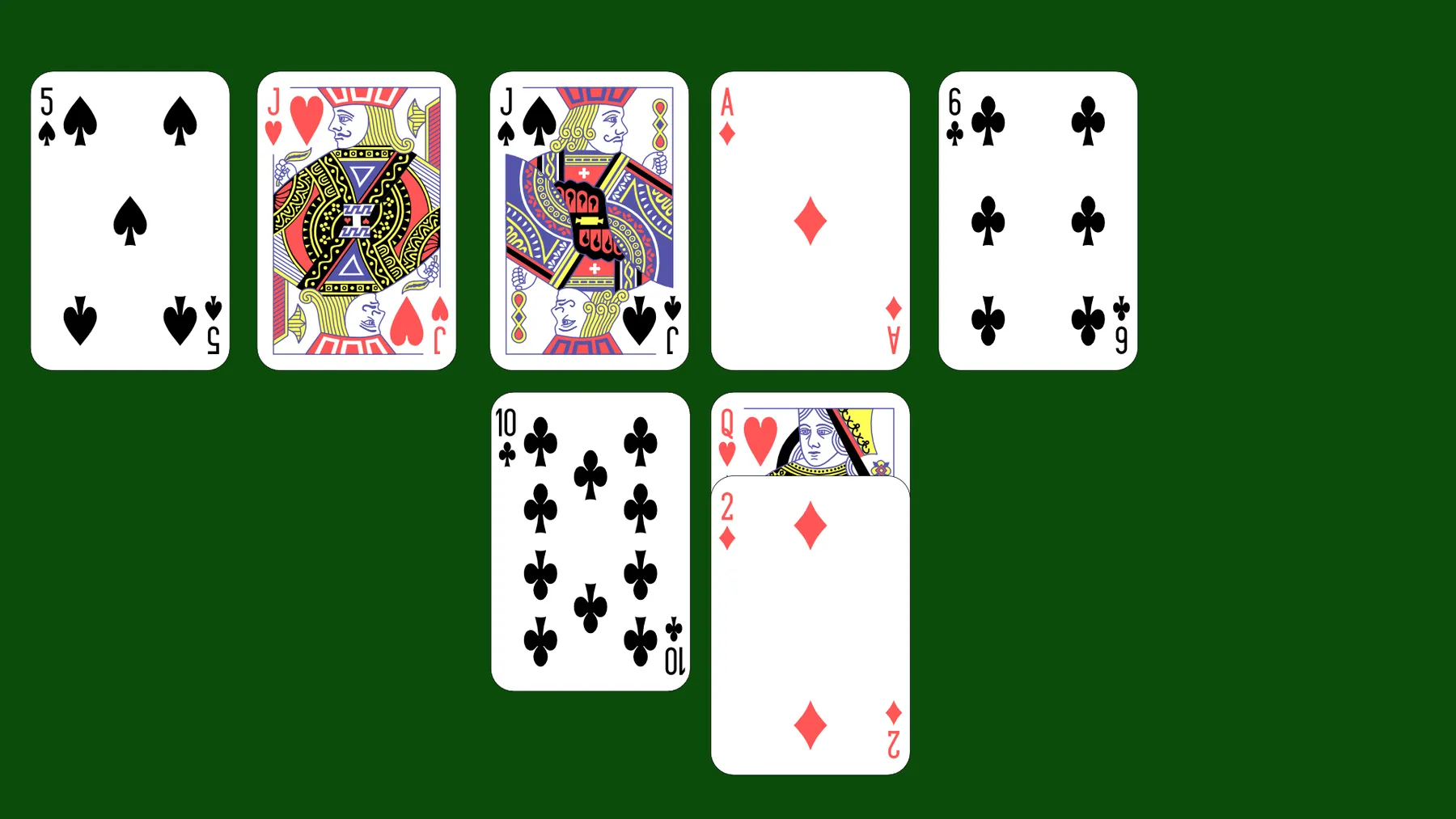

The game uses two standard 52-card decks (ranks 1–13, four suits). The secret rule is a deterministic function of the card being played and the current mainline sequence. On each turn, the player selects a card from its hand (12 cards, replenished after each play) and receives immediate feedback: either accepted onto the mainline, or rejected to the sideline. At each turn, the player may also attempt to guess the rule.

In our benchmark, the maximum number of turns is 30, and the scoring system is designed to reward efficient discovery while penalizing incorrect guesses.

Guessing early yields more points if correct, but each wrong guess costs 2 points. If the score drops to zero, the round ends, as a scientist who had exhausted their resources. The optimal strategy requires accurately assessing one’s own confidence: guess too early and risk costly errors; wait too long and leave points on the table. Let’s also note that achieving the maximum score of 30 is impossible, and even a perfect player will score less than 30 due to the need for experimentation. The best possible score depends on the specific rule and how quickly it can be deduced.

Rule Library

In the original game, the dealer invents a secret rule on the spot (and the scoring system is designed to discourage either trivial or impossibly hard rules). For benchmarking LLMs, we need a fixed set of rules to ensure comparability across runs. We created a library of 26 hand-crafted rules designed to cover the space of rule types (static properties, sequential dependencies, cyclic patterns) while remaining tractable to evaluate. Some rules involve simple card properties (e.g., “only red cards”), while others depend on the sequence of previously accepted cards (e.g., “card rank must be higher than previous card”). The rule might involve rank, suits, color or a combination thereof, and may include positional dependencies.

Here are some example rules from our library, with a tentative categorization:

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Static set property | ”Only red cards”, “Only face cards (J, Q, K)“ |

| Combined properties | ”Only hearts with rank ≤7”, “Only red face cards” |

| Sequential | ”Rank must be higher than previous card” |

| Cyclic patterns | ”Alternate between odd and even ranks”, “Suits cycle: ♥→♠→♣→♦“ |

| Complex conditionals | ”Same suit as previous OR rank differs by exactly 2” |

The full list is available in the Appendix. Each rule is played 3 times with different random seeds (affecting the initial hand and deck order). This ensures every model is tested on the same deck sequences for a given seed, and captures variance in performance when the starting hand differs.

What the LLM Must Do

On each turn, the model gets prompted with the rules of the game and the complete game state: the mainline of accepted cards, the sidelines of rejected cards at each position, its current hand, its history of playing and reasoning from the 3 previous turns, and its history of wrong guesses so far (if any). It must then choose a card to play from its hand, and optionally decide whether to formally guess the rule this turn.

The model is free to reason, but it is asked to output a structured response containing:

- Reasoning summary: A brief explanation of its current thinking;

- Card choice: Which card to play from its hand;

- Tentative rule: Its current best hypothesis about the secret rule;

- Confidence level: A self-reported probability (0–10 scale, where 7 means “I estimate 70% chance my tentative rule is correct”);

- Guess decision: Whether to formally try to guess the rule this turn, or not.

Here is an actual example of a model’s response on one turn:

{

"reasoning_summary": "To test if the rule depends on rank, I play a 4♣ (same rank as the starter 4♠) hoping to see if same-rank cards are accepted.",

"card": "4♣",

"tentative_rule": "A card is accepted if it has the same rank as the previous mainline card.",

"confidence_level": 3,

"guess_rule": false

}

This structure is more than what would be strictly needed for just playing the game, but it also lets us analyze not just whether models succeed, but how they reason:

- Do they update hypotheses appropriately when evidence contradicts them?

- Do they explore strategically or play conservatively?

- Is their stated confidence calibrated to their actual accuracy?

Forcing the model to articulate a tentative rule and confidence level (even when not formally guessing) allows us to secretly evaluate it at every turn, useful for measuring calibration.

Evaluating Rule Correctness

How do we determine if a guessed rule is correct? Simple string matching fails because semantically equivalent rules can be phrased differently: “alternating colors” and “red follows black, black follows red” describe the same constraint. And asking an LLM to judge equivalence risks bias or errors on edge cases.

Instead, we compare rules by simulation. Each secret rule in our benchmark is implemented as Python code. When the model proposes a rule in natural language, an auxiliary LLM translates it into code as well. We then simulate 100 random continuations from the current game state: at each turn, we check whether both rules agree on which cards would be accepted or rejected. Each simulation runs up to 40 turns, testing all 52 possible cards at each step. If they agree on all decisions across all simulations, the rules are considered equivalent.

This approach handles paraphrases naturally, but it also captures something subtler. Consider a game where the true rule is “same color as previous card,” and the first accepted card happens to be red. From that point forward, only red cards can ever be accepted. A model guessing “red cards only” has made a perfectly valid inference from the available evidence; penalizing it would be unfair. By simulating from the current state rather than from scratch, we accept any rule that behaves identically going forward.

Models Evaluated

We evaluated 12 frontier models from seven labs, including both proprietary and open-weight models. Open-weight models were accessed via Hugging Face inference providers. Several models offer configurable reasoning levels, which we indicate when applicable.

| Model | Lab | Provider | Reasoning | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kimi K2 Thinking | Moonshot | 🤗 Inference providers | Default | Open |

| GLM 4.7 | Z.ai | 🤗 Inference providers | Default | Open |

| DeepSeek R1 | DeepSeek | 🤗 Inference providers | Default | Open |

| GPT OSS 120B | OpenAI | 🤗 Inference providers | Default | Open |

| GPT OSS 20B | OpenAI | 🤗 Inference providers | Default | Open |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | Anthropic | Anthropic | 16000 tok. | Closed |

| Claude Haiku 4.5 | Anthropic | Anthropic | 16000 tok. | Closed |

| GPT 5.2 | OpenAI | OpenAI | High | Closed |

| GPT 5 Mini | OpenAI | OpenAI | Medium | Closed |

| Gemini 3 Flash Preview | High | Closed | ||

| Gemini 3 Flash Preview | Low | Closed | ||

| Grok 4.1 | xAI | xAI | Fast | Closed |

All models were evaluated with temperature 0.7 and max tokens of 16,384. Each model played 78 rounds (26 rules × 3 seeds).

2. Results

Overall Performance

Performance is measured as the average score per round. We also report token usage (output + reasoning) per turn to compare efficiency.

Performance varies dramatically among tested models.

-

Claude Opus 4.5 achieves top performance with a score of 17.0 and moderate token usage. The open-weight model Kimi K2 comes second at 16.2, performing competitively with the best proprietary models, but at the cost of a larger reasoning budget. GLM 4.7 also performs well, scoring 15.5 with a similar token count to Kimi K2.

-

GPT 5.2 High and Grok 4.1 Fast Reasoning show similar performance around 15, but GPT 5.2 High is twice as token-efficient.

-

Gemini 3 Flash Preview High scores at 14.0 but with a much higher token count.

-

GPT 5 Mini Medium, GPT OSS 120B, and Gemini 3 Flash Preview Low cluster in the mid-tier (around 13) with low token usage. DeepSeek R1, an open-weight model specialized for reasoning tasks, achieves a similar score but with a much larger token count.

-

Finally, GPT OSS 20B and Claude Haiku 4.5 lag behind, scoring between 11 and 12 with moderate token usage.

As mentioned earlier, this score reflects not only the model’s ability to find the correct rule, but also its metacognitive skills: knowing when to commit, how confident to be, and how to balance exploration versus exploitation. To distinguish these factors, we computed an alternative “no-stakes” score that removes penalties for wrong guesses and counts tentative rules as guesses.

Pure discovery versus metacognition

We use the same game data but apply a different scoring system to reflect the pure ability to discover the rule, without the metacognitive aspect of knowing when to commit. In this “no stakes” scenario, guessing is free and systematic: at each turn, if the model has the correct tentative rule, it is considered to have guessed it correctly (even if it didn’t formally attempt to guess); if the tentative rule is incorrect, it is considered a wrong guess, but without penalty.

The following chart shows the initial score of each model, and which (higher) score it would have achieved under the “no stakes” scenario. This allows us to isolate pure rule-discovery ability from metacognitive skills.

Even if using this alternative scoring does not greatly change the relative ranking of models, it reveals important differences in their behavior.

-

Gemini 3 Flash Preview Low and Kimi K2 have the smallest difference (less than 3);

-

GPT 5.2 High and Claude Haiku 4.5 are the two models with the largest difference between raw and no-stakes scores (more than 4).

There are two possible reasons for the gap between raw and no-stakes scores:

- The model is reckless and makes a lot of wrong guesses, incurring penalties.

- The model is too cautious and waits too long before guessing, it has the correct rule but delays guessing, missing out on points.

We analyze these two aspects in more detail below.

The Boldness Trade-off

To estimate how reckless a model is, we can compute the average number of failed guesses per round. It directly relates to how many points a model loses due to wrong guesses.

To estimate caution, we can compute how many turns the model waits while having the correct tentative rule, before actually guessing it. This relates to how many points a model might lose by waiting too long to commit.

How should we interpret these values? A failed guess costs 2 points, while each turn of delay costs 1 point, so the optimal number of failed guesses per round should be around 0.5 (one failed guess every two rounds) to balance both sources of loss. Most models exceed this threshold, indicating a clear tendency towards recklessness. This is confirmed by low caution values: most models wait around 1 turn or less on average before guessing when they have the correct rule.

-

GPT 5.2 High stands out with very few failed guesses (0.28 per round) but high caution, waiting 3.5 turns on average before guessing when it has the correct rule.

-

Gemini 3 Flash Preview and GPT 5 Mini Medium occupy an intermediate position. Gemini Flash Preview Low achieves a slightly better balance, losing on average 2 points to caution and 2 points to recklessness (about one failed guess per round).

We can summarize this caution-recklessness behavior with a single metric: the boldness index as the difference between the points lost by being reckless (failed guesses) and the points lost by being cautious (delayed correct guesses). A positive value indicates more loss due to recklessness, while a negative value indicates more loss due to caution. This is reported in the following chart.

A way to understand this chart is in terms of missed opportunity. Models in the center achieve a good balance between recklessness and caution, minimizing lost points. They perform at the best permitted by their inductive abilities. Models on the left are too cautious, missing out on points by delaying correct guesses. At identical inductive ability, they could improve their score by guessing earlier. Models on the right are too reckless, losing points from frequent wrong guesses. At identical inductive ability, they could improve their score by being more cautious and guessing less often.

To understand the causes of these different behaviors, we now turn to an analysis of confidence and guessing strategies.

Confidence and Calibration

Every turn, even when they don’t choose to guess, models are asked to output their best tentative rule and their confidence level in it, with clear instructions on what it means (7 = 70% probability of being correct, etc.). When confidence ≥5, we systematically test whether they would have guessed correctly, even if they didn’t formally attempt to do so. This allows us to evaluate calibration: does reported confidence match actual accuracy? This is particularly relevant as neural networks and LLMs in particular have been shown to be poorly calibrated (Guo et al., 2017; Geng et al., 2024; Kapoor et al., 2024).

The calibration analysis reveals several patterns:

- All models are clearly overconfident: for instance, when they report 80% confidence, their actual success rates are often closer to 20%. This mirrors well-documented overconfidence in human judgment (Lichtenstein & Fischhoff, 1977).

- GPT 5.2 High is the best-calibrated model overall, staying closest to the diagonal, though still slightly overconfident.

- Even strong performers like Claude Opus 4.5 and Kimi K2 show significant overconfidence.

Is overconfidence a problem? In our setting, not necessarily, as it depends on how the model acts on it. For a perfectly calibrated model, decision theory gives us the optimal strategy. If your confidence is , guessing immediately saves you 1 point with probability but costs you 2 penalty points with probability . To achieve a positive expected value, we need . Thus the optimal confidence threshold for guessing is 0.67: guess when you believe your tentative rule has at least a 67% chance of being correct. But do models follow such a strategy?

For this, we can look at how often models guess at each reported confidence level. This is shown in the following figure. For each confidence level (from 5 to 10), we compute the guess rate: the fraction of turns the model actually attempts to guess when reporting that confidence.

Once again, we observe significant differences from one model to another. Grok 4.1 and Gemini 3 Flash Low will essentially only guess when very confident (9 or 10). Most other models will also often guess at confidence level 8 and rarely below. The two Claude models show different behaviors: Claude Opus 4.5 tends to guess more aggressively at confidence level 8, while Claude Haiku 4.5 often guesses even at confidence level 7. (Note that from that analysis alone, Claude Haiku has the best strategy since it guesses more often at confidence level 7. This would be optimal…if the model was perfectly calibrated, which is not the case.)

Models are on average more cautious than the optimal decision-theoretic strategy for a perfectly calibrated model, which would guess as soon as confidence exceeds 67%. This actually benefits them, given their overconfidence: by raising the threshold for guessing, they reduce the risk of wrong guesses and compensate for their poor calibration.

This is particularly true for Gemini 3 Flash Preview Low, which is extremely cautious, guessing only 1/3 of the time even at reported confidence 9. This compensates for its overconfidence and likely explains why it has the smallest gap between raw and no-stakes scores among all models. In the “High” reasoning setting, it is slightly more aggressive, guessing more than 60% of the time at confidence level 9.

GPT 5.2 High is both fairly well calibrated and very cautious, leading to very few failed guesses but a high opportunity cost due to delayed guessing. This suggests that GPT 5.2 High could improve its performance by being more aggressive in guessing once it has a correct tentative rule, especially at confidence level 8.

Reasoning effort vs turn count

To see whether models tend to think more per turn when the round is longer, we plotted the average number of output tokens per turn.

The patterns reveal striking differences in how models allocate reasoning effort:

-

Most models show a gradual increase in reasoning effort (token usage) as the turn number increases.

-

Grok 4.1 Fast Reasoning stands out with dramatically increasing token usage, starting around 1,200 tokens per turn and reaching over 20,000 by turn 30. This suggests the model invests more reasoning effort as problems become harder to solve.

-

Gemini 3 Flash Preview Low maintains remarkably flat token usage throughout, staying around 1,000-1,400 tokens regardless of turn number. This suggests a consistent, lightweight reasoning approach that doesn’t scale with problem difficulty.

-

Gemini 3 Flash Preview High very quickly spends a lot of tokens, more than 15,000 after a few turns.

The general upward trend admits two interpretations that we cannot fully disentangle: models may invest more reasoning effort as problems become harder, but we also have survivorship bias—later turns only occur in harder games where the rule hasn’t been found yet. Regardless of cause, the magnitude of increase varies widely, from Gemini’s flat profile to Grok’s 15x increase, revealing genuine differences in how models allocate reasoning budget.

Performance by Rule Complexity

Not all rules are created equal. Some rules are discovered quickly by all models (e.g. “all cards must be red”) while others prove consistently challenging (e.g. “increase rank after a red card, decrease after a black”).

The following figure breaks down performance by rule across all models and runs, displaying the average success rate per rule on the left (how often the rule was found), and individual run scores as colored dots for each model on the right.

It confirms that some rules are consistently easy, with low variance in score across models, while others are hard for all models. To analyze this, we need a way to quantify rule complexity. This is not straightforward since it depends on multiple factors: the inherent logical complexity of the rule, how familiar the concept is to models, and how much evidence is needed to distinguish it from alternatives.

We created a crude complexity score for each rule based on the complexity of its code implementation, as measured by cyclomatic complexity (McCabe, 1976) and Abstract Syntax Tree node count. We combine these two metrics into a single indicator:

The coefficient 0.2 was chosen to maximize correlation with average success rate across models, achieving a correlation of -0.67. This indicates that, as expected, more complex rules tend to have lower success rates, and validates our complexity metric as a useful proxy for rule difficulty, despite its limitations.

The following plot breaks down the success rate of each model per complexity quartile.

Interestingly, code complexity (as measured by our combination of cyclomatic complexity and AST node count) doesn’t perfectly predict difficulty, as semantic concepts also play a role. A rule like “only face cards” has complexity equivalent to “only A, 2 and 3”, but the former is easier for models (and humans) due to familiarity with the semantic category of face cards.

Rules involving rare events also prove challenging. “Only aces” is harder than “only even ranks” despite being simpler, because models need more evidence to confirm it.

This raises an interesting question: are symmetric rules equally difficult? Logically, “only spades” and “no spades” should be equivalent in difficulty, but models might have biases. Indeed, the average score on “only spades” is 25, while “no spades” scores only 20.

Complexity of rules produced

One common failure mode we observed is that models tend to produce overly complicated tentative rules, violating the principle of parsimony (Occam’s razor; Blumer et al., 1987), even though they were informed that rules are typically simple one-sentence statements. They also produce rules that fit all observed data so far, but fail to generalize to new cards because they are more complex than necessary.

As an illustration, here is an example of tentative rule produced by one of the models (Claude Haiku 4.5). The mainline state was (rejected cards are in parentheses)

6♠ 6♦ 9♠ (Q♥) 9♦ (9♣) 7♠ (5♦) (J♦) (A♦) (Q♦) (2♦) (4♦) (9♦) (8♠) (A♠) (10♥) (J♦) (9♥) 7♦ 9♠ (A♥) (8♥)

The actual rule was “Rank repeats in pairs”. The tentative rule proposed by Haiku 4.5 at this stage of the game was:

“Odd-positioned mainline cards must be spades, even-positioned mainline cards must be diamonds. Consecutive pairs of positions must have matching ranks. Additionally, each rank (6, 7, 9) can appear only twice on the mainline, meaning position 8 must be a diamond with a rank different from 6, 7, and 9, or the pattern breaks at position 8 with new rules.”

This is incredibly complicated compared to the actual rule! And as you can read, it does contain the actual rule “Consecutive pairs of positions must have matching ranks”, but adds unnecessary constraints about suits and counts that do not generalize.

To quantify this, we computed the complexity ratio: the complexity of the model’s tentative rule divided by the actual rule complexity, using the same code-based metric described above.

The results reveal a clear tendency toward overcomplication among several models:

- GPT OSS 120B and GPT OSS 20B stand out with median ratios of 1.32 and 1.15 respectively, and wide interquartile range, very often hypothesizing more complex rules than necessary.

- Claude Haiku 4.5 also tends to overcomplicate slightly (1.05) on average, but with high variance and many tentative rules being much more complex than needed.

- Claude Opus 4.5, GPT 5.2, GLM 4.7 and Kimi K2 are the best calibrated, with median ratios close to 1.0 and moderate variance, suggesting they match rule complexity most accurately.

- Most models cluster around 1.0, indicating reasonable complexity calibration on average, but the wide interquartile ranges show substantial variation across individual games.

Summary

Our evaluation reveals substantial variation in how models approach the Eleusis task. Claude Opus 4.5 leads in overall performance, followed closely by the open-weight Kimi K2 and GLM 4.7. All models exhibit overconfidence (reporting higher certainty than their accuracy warrants) but they partially compensate by being more cautious than decision theory would recommend. The boldness trade-off varies dramatically: GPT 5.2 High is extremely cautious (high success rate but slow to commit), while Claude Haiku 4.5 and DeepSeek R1 are reckless (many failed guesses). Rule complexity matters, but semantic familiarity and evidence availability also influence difficulty. Finally, models tend to overcomplicate their hypotheses, particularly the open-weight GPT OSS models, while Claude Opus 4.5, GPT 5.2 High, and Kimi K2 best match actual rule complexity.

3. Discussion

Scientist Personalities

Our results reveal that strong performance depends on two distinct capabilities: inductive reasoning (the ability to find the correct rule) and metacognitive calibration (knowing when to commit). These operate on different axes, a model can excel at finding rules while being poor at knowing when to trust its answers.

The clearest example is GPT 5.2 High. It achieves the highest success rate (95% of rounds eventually solved) yet ranks third overall because of excessive caution. When GPT 5.2 High has the correct rule, it waits an average of 3.5 turns before guessing, costing points that could have been won by committing earlier.

The whole landscape suggests three emergent “scientist personalities”:

- The Cautious Scientist (GPT 5.2 High): High accuracy, hesitant to publish. Rarely wrong, but misses opportunities by over-deliberating.

- The Bold Scientist (Claude Haiku 4.5, DeepSeek R1): Quick to claim discoveries. More wrong guesses, but also faster to capitalize on correct insights.

- The Balanced Scientist (Gemini 3 Flash): Optimal risk-reward calibration. Commits quickly when confident, holds back when uncertain.

Neither extreme is optimal. The cautious scientist loses points waiting; the bold scientist loses points on retractions. The winning strategy requires balance.

This has implications for training. At identical raw reasoning ability, metacognitive skills become a key differentiator. These distinct personalities reveal missed opportunities that might be addressed, for instance through post-training. Models could potentially benefit from training or prompting to adjust their “decision threshold”, when to commit versus when to gather more evidence.

Open vs Closed Models

A notable finding is the competitive performance of open-weight models. Kimi K2 (16.2) and GLM 4.7 (15.6), both open-weight, outperform several proprietary models including GPT 5.2. DeepSeek R1 scores only 13.3, largely due to its reckless guessing strategy. It scores comparably to Gemini 3 Flash but could likely outperform it with better calibration. These results suggest that open models are viable contenders for scientific reasoning tasks, not only proprietary ones.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our library of 26 hand-crafted rules, while varied, cannot cover the full space of scientific reasoning. Expanding it with temporal rules, multi-step dependencies, and other patterns would strengthen the benchmark considerably (but would also likely require many more playing turns). With only 3 seeds per rule, some of our variance estimates remain noisy, and scaling up would sharpen the picture.

We also used a single prompt design and did not explore how different instructions might shift model behavior; it would be particularly interesting to test whether prompting alone can compensate for poor calibration or reckless guessing strategies. Another significant gap is the absence of a human baseline: without it, we lack an anchor for judging whether model performance is genuinely strong or weak in absolute terms.

Finally, our data captures what models guess but not how they experiment: a deeper analysis could reveal whether models exhibit confirmation bias (Klayman & Ha, 1987), systematically preferring cards that confirm their current hypothesis over cards that might falsify it, or other reasoning failure modes.

Conclusion

The Eleusis benchmark offers a window into capabilities that matter for real-world scientific reasoning: iterative hypothesis refinement, strategic experimentation, and calibrated confidence. Perhaps most importantly, it reveals the critical role of metacognition: the ability to accurately assess one’s own knowledge state. These capabilities are as important as pure reasoning ability but rarely evaluated in benchmarks. ARC-AGI 3 might be a step in that direction since it will be an interactive reasoning benchmark. It will be interesting to correlates its results with Eleusis to see if it captures similar dynamics.

Appendix

Greetings

Many thanks to Quentin Gallouédec for his detailed feedback on a draft of this article, and to Leandro Von Werra, Lewis Tunstall and Nathan Habib for useful discussions on the design of the benchmark and interpretation of results.

All 26 rules

| Rule | Description |

|---|---|

| Only red cards | Only red cards (hearts or diamonds). |

| Spades only | Only cards of the suit spades. |

| Alternating colors | Cards must alternate between red and black colors. Any card may start the line. |

| Even ranks only | Only cards with an even rank (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12). |

| Different suit | The card must be of a different suit than the previous card. Any card may start the line. |

| No spades | Only hearts, clubs, and diamonds allowed. Spades are forbidden. |

| Opposite parity | Card rank must have opposite odd/even parity to the previous card’s rank. Any card may start the line. |

| Only aces | Only Aces (rank 1). |

| Different suit, same color | The card must be of a different suit but same color as the previous card. Any card may start the line. |

| Prime ranks only | Only ranks that are prime numbers (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13). |

| Face cards only | Only face cards (Jack, Queen, King). |

| Spades and diamonds only | Only spades and diamonds. |

| Cyclic suit order | Suits must follow: hearts → spades → clubs → diamonds → hearts… Any card may start the line. |

| Ranks 1–7 | Only cards between 1 and 7 inclusive. |

| Black face cards | Only black face cards (Jack/Queen/King of spades or clubs). |

| Alternating face/number | Alternate face and number cards. Any card may start the line. |

| Share color or parity | Each card must share at least one property with the previous card: same color, or same parity. Any card may start the line. |

| Non-decreasing rank | Each card must have rank ≥ previous card. Only Ace can start the line. |

| Ranks 5–9 | Only cards between 5 and 9 inclusive. |

| Red rank ≤7 | Only red cards whose rank is ≤7. |

| Paired suits alternating | Suits in pairs: cards 1–2 same suit, cards 3–4 same suit (different from 1–2), etc. |

| Face red, number black | Face cards (J/Q/K) must be red; number cards (1–10) must be black. |

| Alternating groups | Group A = hearts + spades; Group B = clubs + diamonds. Alternate between groups. Any card may start the line. |

| Red up, black down | If previous card was red, rank must increase or stay equal; if black, rank must decrease or stay equal. Start with rank 5–9. |

| Face card imposes suit | If a face card is played, next card must match its suit. Otherwise, next card must be a different suit. |

| Paired ranks distinct | Ranks in doubles: (x, x), then (y, y) with y ≠ x, then (z, z) with z ≠ y, etc. |

Code

Code is available on Github at https://github.com/scienceetonnante/eleusis-llm-benchmark.